Angelo J. Grinceri III never intended to be a farmer. He left his home in New Jersey for New York City to work in fitness and real estate. But his work for a large developer, learning about taxes and zoning and navigating the intersection between private and state legislation, led him back to his family’s land and roots.

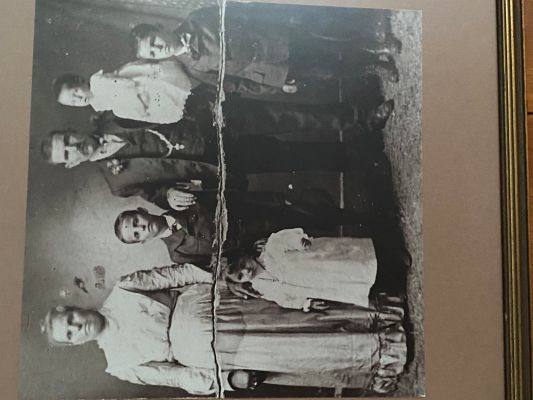

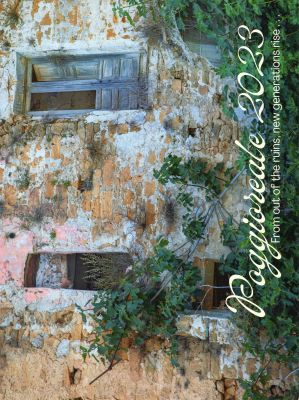

Today, Old Forks Farm has emerged from a plot of land in Hammonton, New Jersey, which Angelo's great-grandfather, Sebastiano Grinceri, once farmed. Born in Castanea delle Furie, Sicily, Sebastiano arrived in the early 1900s aboard a ship out of Messina. At that time, the Atlantic City Railroad owned the property where he found work. He and his wife, Rosa, ultimately embraced the American Dream and purchased the land to grow tomatoes, potatoes, and peaches, as well as to raise pigs.

"On a daily basis, I think about how he left his world and worked for someone else and then had the ability to purchase that land and do something with it," Angelo says.

After much sweat and paperwork, Angelo now oversees 30 acres of about 20 crops, including figs, privacy trees, lemons and oranges, cucumbers, carrots, peppers, peas, string beans, and sunflowers (along with a recently acquired blackberry property, operating under Curated Nature).

In addition to its fresh produce, the Old Forks Farm market sells honey, jams, and bread. They also offer opportunities to pick your own blackberries in July and celebrate with a visit to Santa's Farm Festival on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays in December. The farm hosts onsite kids' workshops and fitness classes and rents space for events and activities, such as weddings and family photo shoots.

Angelo shared his inspiration, experience, farming practices, favorite crop, offerings, and what he ultimately hopes to deliver.

Angelo J Grinceri III with his father, Angelo J. Grinceri Jr.

How and why did you start Old Forks Farm?

Since I was born, my father had been using the property, which he called Old Forks Holly Farm, to operate a small nursery where he grew privacy trees.

When I was around 33, I was watching my dad get older, and I really saw how much time and attention are required for the land to be of value. I felt a massive sense of responsibility. I realized that no one would take care of your things unless you chose to do so.

I decided it shouldn't just be an overgrown piece of land. It should be something that's curated and taken care of. That became a driving force behind everything that I was doing. It was the emotional and financial driver because I equated a lot of my purpose to revitalizing and rebuilding that farm into something that could be really special.

It was interesting because our farm, which is now very legal, wasn't actually a legal, tax-identified farm. The first thing I did was contact the USDA, and I found out what was required to make it a farm again.

The property had a few issues. A large part was overgrown by woods, and another, which was a big issue, was that there was no more topsoil in the area that was to be farmed. It was gravel and sand.

Apparently, over the past 30 or 40 years, there was a lot of wind, and there wasn't a wind barrier of trees. All that topsoil got blown away and wasn't managed appropriately.

The first thing I did was work with the USDA. We created what's known as a farm conservation plan. That was the first step in becoming a legally identified farm. It gave us access to the USDA's professionals and expertise. It helped us understand what to do with the soil and what that property specifically needed: a lot of soil regeneration.

One of the most natural ways to regenerate the soil is to take in leaves like decomposing plant matter. You can't accept those things onto your property in New Jersey unless you are cleared and registered with the New Jersey DEP. We had to go through this whole approval process to be able to accept leaves from different towns and local municipalities because leaves from a town are considered a waste product. We did that, and we've been working with them since 2020, really focusing on that.

Angelo worked with the USDA on a soil regeneration program.

What farming practices have you employed?

The first and biggest thing we did was figure out how to bring water throughout the entire property. We had to run large main-line irrigation systems.

The second thing was soil regeneration. So the soil regeneration program that we did with the USDA consisted of three different parts for about four years: collecting leaves, letting those leaves decompose for two years separately in a pile, and then spreading those leaves throughout the property every year. We did that with a manure spreader.

We also plant cover crops. Tillage is a large part of what destroys soil health. Say you plow and overturn the soil, and there is no covering over it. What you'll see in most conventional farms is that they'll go through their summer crop and then till the soil in the fall right before the winter, leaving the soil bare all winter long.

Winter is the windiest time, so all that soil is being blown and also dried out. The wind also dries out the biochemistry of what makes healthy soil.

One of the practices that we really took on was cover crops. As soon as we're done with the crop season for the summer (or even the fall, sometimes), we plant different types of things over the entire property. We chose different species that would also cover nutrient regeneration.

The third thing is that we planted a wildflower field. The USDA had a specialist come to identify the specific wildflowers and collection of plant flowers that would best support bee pollination. We had to get a custom-made seed mix, and it was a blend of 20 different native species. This special blend of these fine seeds was a pain in the butt to plant, because I had to plant them by hand. But we did that to generate a healthier bee population, which would help pollinate everything we have fruiting.

The USDA is fantastic if you choose to work with them. They have all the right tools and people at a farmer's disposal to help transition to organic farming, figure out soil conservation, and follow all these practices. You have to be willing to spend the time doing the office hours and applying for the contracts, but it's completely worth it.

That being said, last year, we started a process for organic transition. They have a specialist come out, identify what you're doing, look at your space, and write up a plan that has to be executed over three years, held consistently for three years, and rigorously checked up on for three years to become organic-certified.

Old Forks Farm's fig trees are a nod to Angelo's heritage.

Do you have a favorite item among the farm’s produce and products?

I identified with figs for a long time because they're a specialty crop specific to Italy, and no one is commercializing them locally. Figs grown commercially on the West Coast, for example, are driven by commercial practices, which drastically change the taste and texture of a fig.

Our figs are phenomenal, and anyone I've given them to is very excited to share that they are the best figs they've ever had. They're usually willing to pay twice as much for them because of their value and quality. And it very much feels like I'm paying homage to my ancestry.

Book an Old Folks Farm workout class or bring the kids to Santa's Farm Festival.

Tell us about your workshops and how these connect the farm with the community.

The workshops we've done so far have always been kid-focused. We'll have kids come in and learn how to plant a vegetable. So they'll walk home with a tomato or strawberry plant. It becomes this interactive thing where they design their cup or get their hands dirty. Then, we offered a Christmas series called Santa's Farm Festival.

Santa's Farm was awesome because we put lights on all the tractors, and the kids walked through this lit-up pathway. They were walking in between all the tractors and went through this greenhouse that we called the "candy cane forest," which was a tree nursery. They came around into another greenhouse, which was a maze of trees. And they found arts and crafts hidden in this maze. One craft they did was to decorate a hat, like a Santa hat, and they would put their name on it along with little decorations. After that, they would get to the next station, which was designing a cookie. They would decorate a cookie, get Christmas cookies, and then go through the maze some more and find Santa. They would just freak out because it was a big surprise that Santa would be there.

Santa with a little helper.

I know that's not a farming workshop, but it was the ability to celebrate Christmas in a different setting than what they were used to, while getting comfortable being on a farm. They're walking through dirt and greenhouses, part of our functioning farm property. People say, "Oh, wow, I didn't know that that was how this was done," or "I didn't know this was a thing." So that's been really nice.

This year, we're looking at launching a proper one or two-day-a-week kids' camp where they come and do farm chores for the day and play farm games. That's still in the ideation phase. But that is a goal of ours for the future. We've seen a few other farms do it, with parents raving about the principles and work ethic it instills in the children. It becomes regular if they're coming once or twice a week every week. Imagine how much of a difference that makes in their personality over the summer.

Jessica Eme and Angelo with Gator.

What do you hope to share?

Living in New York City for so long, the farm has always been a safe space for me, where it really allowed me to get out of my head and out of the hustle and bustle of work life. I guess simultaneously, meditation was becoming very large.

I started to realize that the practice of farming is a form of active meditation because you're present. You're actively present when you're doing something. In meditation, the biggest thing they're trying to teach you is how to be present. But you're in a seated meditation class; you're present with doing nothing, right?

The farm has taught me to be very present in the doing, not just in stillness. And I found that to be wildly transformative. There's action and proof that you had intention in what you were doing after spending a day working the land. You can see a physical change. Regular seated meditation doesn't really offer you that. This feels a little bit more purpose-driven for me.

When you're present within the biosphere of a farm, there are so many different things in play. There's the environment, the weather, the soil, insects, rodents, and reptiles—all these different things, and every single thing makes a difference.

I thought that it was such a beautiful observation of life in general. So, all being said, I also have a hatred for convenience. As a society, we're trending towards extreme convenience, where we don't have to cook our food if we don't want to. Commuting is very easy with ride shares and that kind of thing. There's just a lot of wisdom in coming back and learning about how things once were, how things are made and created, and how the earth works. So I try to really share that.

Angelo J. Grinceri III with Laurelette

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!