Rosetta Costantino's deep connection with food began in her early years in Verbicaro, a wine-producing hill town in Calabria. Her father was a master cheesemaker and winemaker, and her mother and grandmother grew vegetables, baked bread, and made pasta from scratch. Their ability to live off the land and produce simple yet delicious cuisine characteristic of the region inspired Rosetta.

That passion followed her to San Francisco, where her family emigrated when she was a teenager. It sustained her during her college years at the University of California, Berkeley, and into her career as a chemical engineer. It was always there in the background until she started teaching cooking classes after 20 years of working in Silicon Valley.

Rosetta had a chance encounter with San Francisco Chronicle food writer Janet Fletcher, who wanted to know more about Calabria's food and culture. Once that article, "Calabria from Scratch," was published, Rosetta's phone started ringing, and she suddenly had a vibrant business offering cooking classes.

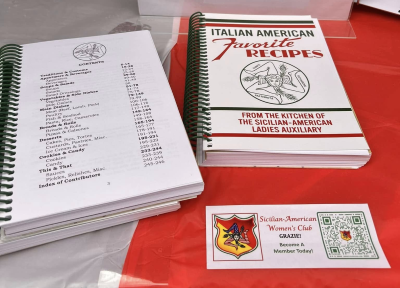

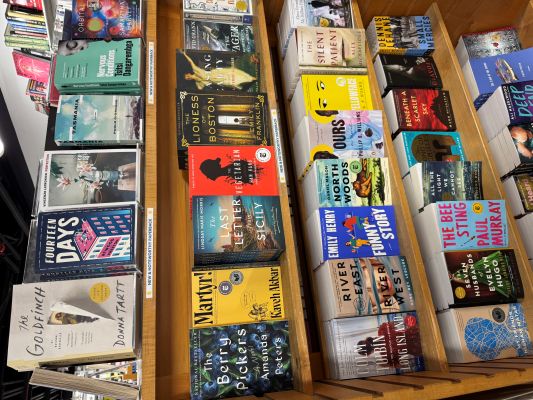

She teamed up with Janet to write a cookbook, My Calabria, which was published in 2010 by W.W. Norton and nominated for an IACP cookbook award. Three years later, she published her second cookbook, Southern Italian Desserts, with Ten Speed Press, which was also nominated for an IACP cookbook award.

Rosetta described her early experiences and how they inspired Cooking with Rosetta, her cooking classes and culinary tours of Southern Italy.

Tell us about your upbringing and how that shaped you.

I grew up in a small, agricultural town in Calabria. Both my grandparents and my parents literally lived off the land. My dad was a winemaker. He had vineyards, but he was also a master cheesemaker. They grew everything, so we really didn't buy anything when it came to food.

I spent a lot of time with both of my grandmothers, and that's really where the love of cooking started because I wanted to be with them in the kitchen. When I was four or five years old, they would let me do simple tasks.

I was nine when I first learned how to make homemade pasta. My mom taught me, and then it was kind of more of an "I can take care of myself, I know how to cook" attitude. And it just stayed with me.

When we moved to California, my parents brought all their seeds, and my mom even brought her bread starter in her purse. So they were very set in their ways. It was like, "This is how we're going to eat," and "We'll do whatever we have to do to find what we need," which in a way was great because if they had blended in, I probably would've lost a lot of that.

They started growing all the vegetables. My dad made all the salumi because he was also a master butcher, and my mom tried to figure out how to make ricotta here. We canned our homegrown San Marzano tomatoes from the first summer we were here. So all those things stayed.

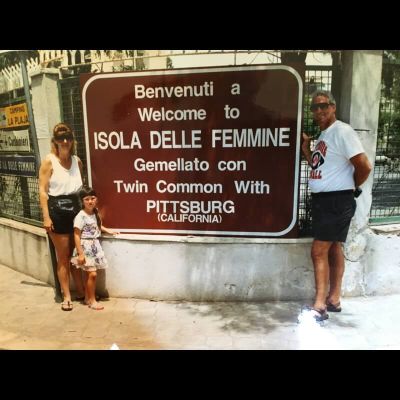

I always tell people in my cooking classes that California was where I learned about the rest of Italy because I only really knew about the foods of my town. I didn't even know the food outside of Calabria. It's so different from my town. We had neighbors from Northern Italy and Puglia, so I kept learning. And then I met my husband, who is from Sicily. So that got me into a totally different cuisine than I've been exposed to.

What led you to start Cooking with Rosetta?

I just kept learning on my own because I loved it, and it was my favorite hobby. But I didn't go into cooking or culinary school or anything. I went to UC Berkeley, graduated with a chemical engineering degree, and landed a job in Silicon Valley. My career was in high-tech in Silicon Valley, and I used to travel a lot. Any time I would travel, it was always about food for me.

My husband gave me Julia Child's set of French cookbooks. Again, that was foreign to me. I only knew about Italian food. I cooked through all those recipes and just kept learning on my own.

I had two kids, traveled a lot, and worked what felt like 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I decided I would quit in 2001, but they didn't let me quit. I ended up working from home, and during that time, I said, "I want people to know about the foods that I grew up with."

Even today, in the Bay Area, in San Francisco, there's nothing that I call authentic Italian. It's more what I call California Italian. I really wanted people to know about the foods that I grew up with and about Calabria because I felt no one even knew where Calabria was. I decided to teach two cooking classes just for fun. That was 2004.

I never thought it would lead to this. Janet Fletcher, a well-known food writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, heard about me and called me.

She said, "Would you mind if I interviewed you? I heard that you are from Calabria. I don't know anything about this region and its foods."

She came over and spent the day with my mom and me, and we fixed a bunch of recipes. Then she said, "I want to write an article."

I told her I would like to teach two cooking classes because no one knows about the foods I grew up with. And she said, "Oh, you should list them in the article."

I said, "I don't know if anybody will even show up because most people don't even know where Calabria is."

She said, "Do you know how many people wear Italian hats? They've never even been to Italy. They claim they're Italian chefs who cook Italian food. This is the real stuff. You should do it. This is the Bay Area. There are a lot of foodies here, and people might be really interested in learning something they've never heard of."

I said, "OK, I'm only going to do two classes. Go ahead and list them."

A day or two before it came out, she called me and said, "We're ready to go to print, but I think you should include your phone number if you want to sell those two classes."

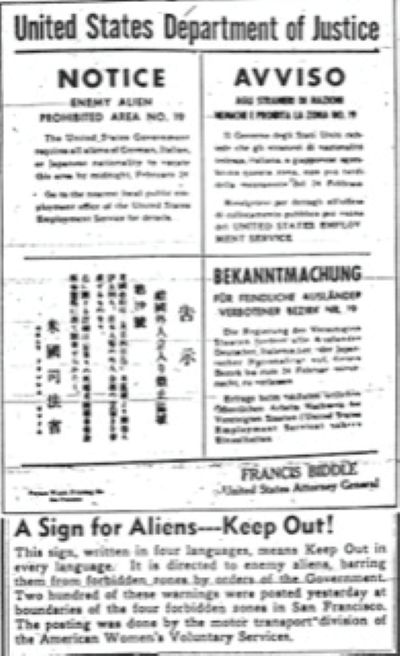

I said, "My phone number is not listed. I really don't want to list it in the paper." She said, "Not everybody has access to the internet. " This was 2004, so I said, "OK, fine."

I still remember that first morning because I had not seen the article, and the phone rang at 7:00 a.m. I was trying to get the kids ready, and that morning, I was going in to work.

I picked up the phone, and an older gentleman was just thanking me. "It's like the first time I've ever seen an article about Calabria and its food." He started telling me about his grandparents and how they used to make this and that, and I said, "Can you call me back?"

The minute I hung up, I remember I went across the hallway to wake up the kids, and the phone was ringing. I said, "Kids don't answer the phone. The article came out, and people are calling about the classes."

I was inundated with phone calls and emails, which kept me busy for two weeks, because the article went around the country. We ended up taking in 200 people: 10 classes, 20 per class. The classes sold out right away. I kept adding and adding, then said, "OK, that's it. This is going to take me into November."

I really did not expect the response that I got from that article and the number of emails. All these people were writing to ask if I knew their relatives or if they knew what this dish was. That gave me the idea of the cookbook because there was nothing written about Calabria at all.

I said, "I need to get all these recipes down, Mom." With everything that my mom made, of course, nothing was written down; everything was just in her head, so you'd cook and taste as you go along.

Norton bought the rights in February 2005. I started teaching in September, put the proposal together, and worked on it. When the book came out, it was supposed to come out in 2008. But then, because of the financial crisis, they held it, so it was published in 2010.

I did my first culinary tour that year. Of course, we had planned it in 2009 because my students were hearing about Calabria. I would bring products back from Calabria, and they would get to taste them. And they would go, "Will you take us?" I said, "OK, I'll do one tour."

We did one and a second. Then my husband came on the third, and I said, "I'm not doing any more tours by myself."

When he came with me, and everyone got to meet him, they found out he was from Palermo, Sicily, and they went, "Oh, why don't you take us there?" So they convinced us to do the Sicily tour.

During that time, my agent twisted my arm to do book number two, Southern Italian Desserts. In that one, we covered all five southern Italian regions.

Then, that was it. I said, "That's it—no more books." And I did quit work, and then I just focused on the culinary tours and the cooking classes.

We also ended up doing Puglia, and almost all of my guests have gone on all three tours.

Guests sit down after a Borgo Saverona, Calabria, cooking class.

What can attendees expect from a tour?

If you were to talk to anybody who has gone with us, they would tell you that they get to see it from someone from the place. So you're not getting a lot of touristy food or following the tourist track. It features a lot of people that we know that you would never meet. So it's authentic, whether in Calabria or Sicily, as far as what people would eat. And that's what I want them to try. So I am not going to serve you a steak because we don't eat steaks. It's not part of our cuisine. They try all the specialties of the areas we visit.

With the Calabria one, we tend to visit more wineries because I wanted people to get to know the wines, which are not very well known. For seven years, I just did a culinary tour, where we had two cooking classes, and then there were one or two wineries. Then, in 2017, I changed it to a wine tour. So we visited two wineries every day because I wanted people to get to know all the indigenous varietals. We sold out two years in a row.

By the third year, a bunch of people started writing to me, saying, "I wish there could be more cooking." So I changed it to a culinary vacation tour, removed two wineries, added cooking classes, and have sold that every year since then.

We did the same thing in Sicily. We stay at Planeta, so they make wines. We get to taste all their different wines and visit Donnafugata, where they get to taste their high-end wines. We go to Cantina Florio in Marsala and visit Cantine Barbera, a local winery run by Marilena Barbera in Menfi. It's a woman-run winery; she makes great organic natural wine. But the tours are all based around food.

We go to the salt pans and taste salt in Sicily. In October, we get to watch the whole process of making extra virgin olive oil and taste it. We also visit Maria Grammatico and take a cooking class with her.

I tell people it's a culinary tour. It's not just a tour to a museum or going to galleries; we do that, especially with Sicily, because there's so much to see there. Of course, we also incorporate that into it, but a lot of emphasis is on the food.

In Sicily, they get to try all the street foods of Palermo and the traditional dishes of the area. Calabria is sort of the same thing. We move throughout Calabria, and the food is very different. We go to the wine region and right to the border with Basilicata and the Pollino National Park area. Then, we go down to Tropea and Spilinga, where they make nduja. They get a feel for the entire region in Calabria, whereas Sicily has just so much to see and do that I would have to do two separate tours: the east and the west. So, we cover the western side of Sicily.

In all my tours, we also visit a local shepherd/cheesemaking place so my guests can taste fresh, warm ricotta as soon as it's made, and of course, the other cheeses they make. This is a unique experience that nobody gets to have in the U.S., as ricotta is not made the same way in Italy.

Cleaning anchovies in Calabria

What are your favorite dishes to introduce to your tour participants?

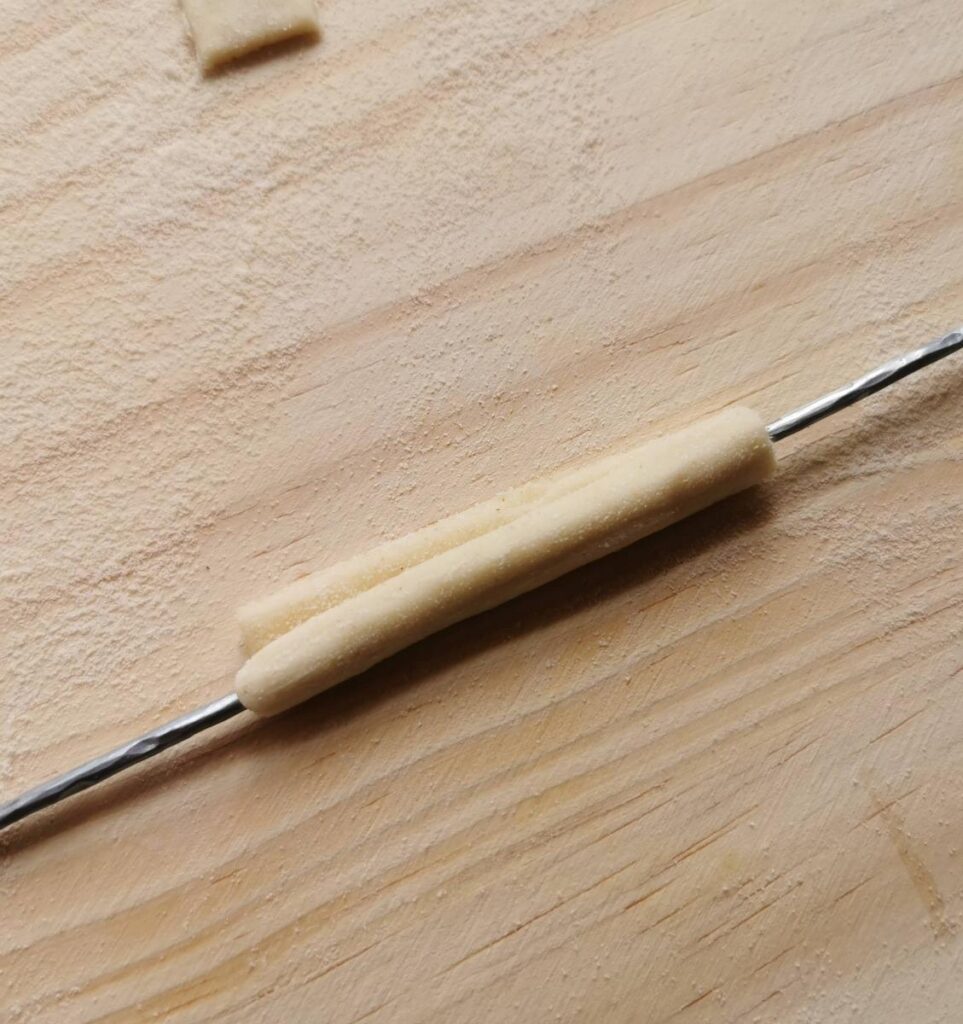

A lot of them are in My Calabria. They get to have the traditional Calabria pasta, which is shaped with a knitting needle. In my town, they're called fusilli. But for most people, the Italian name is maccheroni al ferretto. I take them where they make the nduja so they can see how it's made. And then we have dishes with nduja.

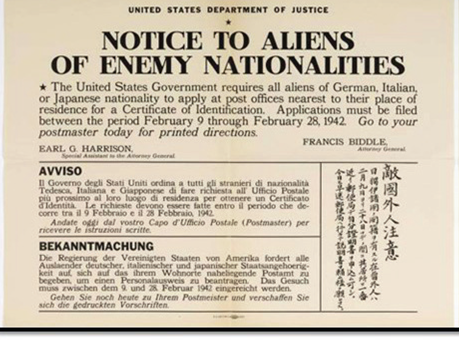

We eat a lot of seafood because Calabria is surrounded by the sea. Also, I have them clean fresh anchovies because most people think of preserved anchovies. Fresh anchovies and fresh sardines are totally different. So, in one of the cooking classes, they clean anchovies, and we make a dish with anchovies, which is also in my book. They're layered with flavored breadcrumbs and baked.

They have baccalà and many vegetables—peppers, eggplants, tomatoes. We do polpette melanzane, which are eggplant meatballs, but there's no meat. Another traditional dish is potatoes and peppers, which you find throughout Calabria. I also try to get them to have baby goat.

We do wild greens. We do a salad of purslane. I have octopus on the menu, too.

Depending on when we go, usually in the fall, they get to taste porcini, the wild mushroom. I base the menus on whatever is in season.

We do the same thing in Sicily. We do one night more Michelin-style just for fun, so they see you can have your traditional and you can have sort of invented dishes. We do two cooking classes with Angelo Pumilia at Planeta's La Foresteria. He is an amazing chef who can do everything from Michelin-style to traditional cooking. But we do very traditional because I want them to learn how to make those dishes. We'll do the caponata; we'll do the arancini; we'll do the cassata; we'll do the busiate pasta by hand. We do all things that are traditional in the area.

A visit to Capo Market in Palermo for seasonal ingredients

What's been the response?

People are surprised, especially by Calabria and its wineries. They don't like that they can't get a lot of the wines in the States because they would definitely buy them.

And most of the people have never been to Sicily. When they see Palermo and what it has, it just blows them away. In terms of Monreale or Palazzo dei Normanni, it's just the beauty of what's there; it's unbelievable. People don't expect that. They think that of Rome and Florence in Italy, and that's where everything is. People are surprised when they see what I say are the jewels we have in Sicily and these amazing temples that are better than those in Greece.

People just love the people and the places we visit more than anything else. Everywhere we go, there are people who are dear family friends, so it doesn't feel like you're a tourist.

Guests finish a cooking class in Altomonte, Calabria.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter for more content and updates!